News from Budock Vean

The Story of Budock Vean’s Pioneer Movie Maker Owner

In 1930 after a visit to the then deserted manor house known as Budock Vean two men decided to purchase it and turn it into an award-winning hotel. Those men were Eddie Pilgrim and Harry B Parkinson. Eddie was an architect by trade, and was the first to spot the neglected building’s potential, but his friend Harry had a very different background, one that brought a little glamour and something of the movie industry sparkle to this quiet corner of Cornwall.

Mr Harry Broughton Parkinson, known as ‘Parky’, was born in 1884 in Blackburn, Lancashire to a working class family but by the age of 35 he had become a pioneer of British silent films. He developed a fascination with moving pictures at an early age and in 1915 began working in a cinema in Brighton, the first cinema in the area had opened only five years earlier. By the time his son Roy was born in 1916 Harry was the manager of the establishment, and it was in this cinema that he had a chance meeting with someone who worked at Teddington Studios in London and secured his first job working in the movie industry.

Harry honed his skills as a writer, director and producer at Teddington Studios and then went on to work for the likes of Fox and Master Film Company. Between 1918 and 1930 he clocked up more than 130 film credits as a producer and director. That equates to about eleven movies a year for twelve years! A tremendous output.

One of his colleagues, the scriptwriter Mr Norman Lee, described what it was like working with him in 1929:

“Mr Parkinson is a vital, hard-working man, quick thinking, authoritative and an expert on motion pictures. A strict, hard-fisted employer but one who gains respect by his supreme knowledge and understanding of human weakness. He is extraordinarily patient and a good listener. On location he rarely interferes but usually sits pensively behind the camera watching sleepily. At the first error he is on his feet and putting things right. He works a good 16 hours a day and no matter how late he is on the floor the previous day he is down in the office by nine in the morning . . . Parkinson is going to be a powerful influence on the British film industry.”

In 1922 Harry set up his own production company called ‘Parkinson Productions’ and made a series of short documentary type films, many focusing on London life, including Wonderful London, London’s Famous Cabarets, Across the Footlights, Romances of the Prize Ring and London After Dark. In fact, Harry was credited with changing the laws that restricted filming on the streets in London. The Burnley News newspaper reported in 1929 that Parkinson had raised questions in Parliament, petitioned the Prime Minister and even had a private interview at Scotland Yard which resulted in the freedom to film at some of the capital’s most iconic locations, which had previously been prohibited.

One of his later films ‘Rock of Ages’ filmed in 1928, was set partly in Cornwall. However, while they were filming some exterior scenes in the fishing village of Polperro Parkinson ran into some difficulties that were later reported in the papers. At first everything went well, the crew were setting up the various cameras, lights and equipment in the picturesque streets surrounding the harbour, the actors were said to be looking more like wily seadogs than the amused local fishermen watching the goings on and Parkinson was able to hire the fishing boats he needed for the shots with ease. There was only one problem – there was no fish! Harry is said to have scoured the village for a haul of fish but none could be found anywhere. In the end he had to buy some from Billingsgate seafood market in London and have it transported all the way down to Cornwall!

In 1926 Parkinson produced easily the most controversial film of his entire career. Called ‘The Life of Charlie Chaplin’ the production was an intimate look at the childhood and rise to fame of the era’s most famous silent movie star. Chaplin, who was by then a world renowned comedy icon, had been born into a poverty stricken household in South London and his childhood was fraught with hardship. His parents were estranged, he had spent time in a workhouse and then a school for destitute children, his mother, Hannah, had been committed to a mental asylum while his father died of alcohol related illnesses.

It is unclear how much of this was included in Parkinson’s film, probably very little, but understandably Chaplin was against any biography of his life being widely distributed, especially without his prior approval. In addition to this the timing of the film could hardly have been worse. Unfortunately it coincided almost to the day with the news of Chaplin’s rather messy divorce hitting the front pages of the newspapers across the globe. Chaplin’s lawyers took legal action and blocked the movie’s release.

Beyond the details of his childhood that he might have preferred to keep private, Chaplin also had a number of other objections which are outlined in the numerous letters and affidavits that survive concerning the case. There were copyright concerns, complaints that the film had been promoted in such a way that it gave the impression that it had been approved by Chaplin himself and it seems the star was also personally affronted by how he had been played in the film.

Since achieving his fame Chaplin had been plagued by imitators, though often meant as flattery, he apparently hated it and felt that Chick Wango, the actor playing him in Parkinson’s film, was just another irksome copycat and a very poor one at that, overacting and making a caricature of his mannerisms. The court case rumbled on for months but in the end the film was mothballed for good and was never shown in public.

In 1997 the only known surviving copy of ‘The Life of Charlie Chaplin’ by Harry B Parkinson, a 38 minutes long black and white movie on 35mm film, sold at Christies Auction House in London for £17,250.

Harry B Parkinson may have been a pioneer in the film industry in the 1920s but all his films were silent and the industry was on the brink of something new – ‘the Talkies’. And Harry, it seems, was not ready for the change and decided it was time to fold away his Director’s chair.

In an interview in the 1960s he explained:

“If you belong to the present generation of cinema patrons, you may have no idea of the revolution brought about in the industry by the invention of ‘talkies’. I worked within the early film industry and the idea of a moving picture fascinated me but a talking picture seemed to reach the limit of imagination. I could not compete with this invention, so I abandoned my interest in films and looked for new worlds to conquer.”

Those ‘new worlds’ ended up being a country house hotel in a quiet corner of Cornwall. Harry threw himself into his partnership with Eddie Pilgrim and seems to have been very hands on with the design of the Budock Vean Hotel.

“At that time [1930s] there were very few quality hotels outside of towns and this was perhaps the first of what was to become a new and very popular classification of hotel. In my former work producing and directing films I spent half my time in hotels – good, bad and indifferent. Many a time I had been annoyed, mostly by little things, which I felt ought never to happen in a well-run hotel. Now my chance had come!”

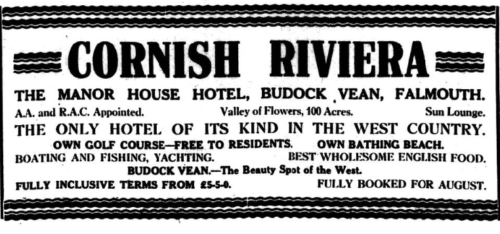

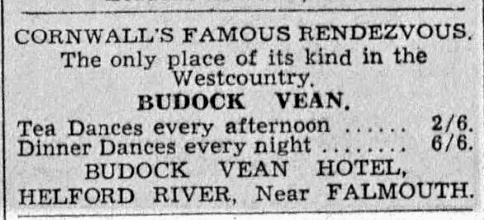

Parkinson’s ambitious plans for the ideal hotel were realised when the Budock Vean received awards from the A.A, R.A.C, Hotel and Restaurant Association and the Wine and Food Society soon after opening in 1933. The hotel was advertised as “Cornwall’s Famous Rendezvous” throughout the 1930s, with tea dances every afternoon and dinner dances every night.

And Parkinson’s show business connections also brought some famous guests to Budock Vean including Charles Moss Woolf who financed some of Alfred Hitchcock’s films, the director of the London Palladium, George Black, Reginald Bromhead, the film producer and the author Virginia Woolf.

In an article in the Illustrated Sporting & Dramatic News in 1938 the author, Ashley Courtney, wrote of “Mr. Harry Parkinson, the enterprising proprietor” who “believes that his inclusive terms should include everything that a guest will want . . .” As well as “the comfortable and well-equipped bedrooms” there were boats for the guests’ use, an excellent golf course, sheltered gardens to walk in, dancing every night and a Lido constructed by Mr Parkinson himself for the purpose of bathing in the river. The hotel even employed its own fishermen “who in addition to taking the guests on fishing expeditions supply the hotel with all its fish.”

The thoughtful finishing touches, the attention to detail and the finer things that Harry Parkinson carefully introduced are what made the Budock Vean an instant success in the 1930s and continue to be the hotel’s philosophy to this day.